Overview

What is the rotator cuff?

The rotator cuff is the group of four tendons that surround the shoulder joint and connect the muscles of the upper shoulder to the bones. Working together as a unit, they help to stabilise the shoulder, particularly during rotating movements. The individual tendons of the rotator cuff are the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor and subscapularis. The commonest tendon to tear is the supraspinatus, while the tendon least commonly torn is the subscapularis.

What are rotator cuff injuries?

The three most common conditions that can affect the rotator cuff are tendonitis, impingement and tears.

Rotator cuff tendonitis occurs when the tendons become inflamed due to irritation. This most often happens due to the overuse of repetitive movements. In some cases calcium can be deposited in the rotator cuff, leading to calcific tendonitis. Treatment for tendonitis includes rest, painkillers, anti-inflammatories and physiotherapy. In some severe cases, keyhole surgery may be needed. Rotator cuff impingement is the pinching or rubbing of any of the four rotator cuff tendons against the top of the shoulder blade. This condition and treatment for it are described in greater detail in the section on subacromial impingement.

A rotator cuff tear is an injury to one of the four rotator cuff tendons.

Why do rotator cuff tears happen?

One (or less commonly, more) of your rotator cuff tendons may be torn as a result of a traumatic event, such as a fall on an outstretched arm. A tear may suddenly occur when you try to lift or catch a heavy object. It can also happen due to overuse, such as too much repetition, especially after a period of inactivity. Tears can be age related and can be put down to some extent to wear and tear. If you suffer from subacromial impingement, you may also be more likely to experience a tear in one of your rotator cuff tendons.

How common are they?

Rotator cuff injuries and inflammation are one of the most common causes of shoulder pain. Rotator cuff tears are more common in people above the age of forty although they can occur in younger people. Tears in younger people are usually caused by an accident. In older people, tears are most commonly caused by impingement. Tears of the tendons are common in the "normal" population and it has been shown that as many as 30% of all 60 year olds may have a tear of the tendon. However treatment is only necessary if it is causing symptoms such as pain or weakness.

Symptoms

The most common symptoms are pain and weakness in the shoulder and arm. Pain is most frequently felt over the front of the shoulder and on the outside of the upper arm. Certain movements, such as raising the arm above shoulder level or behind the back, can significantly increase pain.

Many people with rotator cuff tears complain of particular pain at night, often radiating down the arm. This can cause problems with sleeping.

It is important to report any symptoms of neck, shoulder, upper arm or hand pain to Mr. Cole. In addition, remember to tell him if you feel pins and needles or tingling in your arm or hand. This is because they may indicate that the pain is coming from your neck, via the nerves in your arm.

Investigating the problem

Physical examination

Mr. Cole will talk to you about your shoulder symptoms and your shoulder's history. He will examine your shoulder and look at areas such as your range of movement. He will specifically assess the strength of your rotator cuff tendons and muscles with clinical tests.

Ultrasound or MRI

If Mr. Cole suspects that your tendon is torn, injured or inflamed, he will request an ultrasound scan or an MRI (Magnetic Resonance Image). Both of these scans show the tendons and can highlight any damaged areas.

An ultrasound uses high frequency sound waves to produce images of the body. The procedure is painless and is particularly useful for muscle and tendon injuries.

MRI stands for Magnetic Resonance Imaging. It uses a powerful magnet to obtain three dimensional pictures of body structures. Sometimes it is necessary to inject the shoulder area with a dye to enhance the quality of the MRI "picture". Like ultrasound, it is a non-invasive and painless procedure. It may give a little more detail with regards to the size and potential reparability of any torn tendons.

Photo by Ikonoklast_Fotografie/iStock / Getty Images

Treatment options

Non-surgical treatment

With relatively minor tears the symptoms may settle with with some rest and avoidance of overhead and repetitive activities. Painkillers will help reduce your discomfort. Ice and anti-inflammatory medication will also help reduce the swelling and any pain caused by the swelling. An injection of steroid around the tendon may also help to settle the inflammation.

Physiotherapy

Your team of physiotherapists will create a programme of exercises designed to build the muscles in the rotator cuff. Additional muscle strength will help you to support your shoulder while your symptoms settle. . If one tendon is torn, the remaining three can compensate for it, maintaining much of your shoulder's motion and strength.

Injections

Some anti-inflammatory medications, such as steroids, are best administered directly to the site of the inflammation with an injection.

Surgical treatment

If your shoulder does not respond to rest and physiotherapy, or if the tear is large, you may need surgery. Mr. Cole will advise you on what type of treatment would best suit you and your situation. This may be an arthroscopic procedure (camera keyhole surgery), open surgery, or occasionally a combination of the two.

Surgical rotator cuff repair involves removing scar tissue and stitching the torn tendon or reattaching it to the bone. Surgery is only possible if the tendon has not retracted beyond a certain point. The scale of the repair will vary according to the type and amount of damage to the tendon. Mr. Cole will discuss your surgery with you.

Exercises

Following your surgery, your team of physiotherapists will work with you to devise an exercise programme. This will be designed with advice from Mr. Cole to help you recover as quickly and efficiently as possible.

Surgery

What is the rotator cuff?

The rotator cuff is the group of four tendons that surround the shoulder joint and connect the muscles of the upper shoulder to the bones. Working together as a unit, they help to stabilise the shoulder, particularly during rotating movements. The individual tendons of the rotator cuff are the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor and subscapularis. The commonest tendon to tear is the supraspinatus. The tendon least commonly torn is the subscapularis.

About rotator cuff repairs of tears

The operation aims to reattach your damaged tendon (or tendons) to the bone. Sometimes the tear is too big or the tendon is too fragile for this to be possible and only a partial repair can be achieved. The repair involves sewing the torn tendon into an area called the footprint on the humerus bone. It is sutured to the bone using anchors placed into the bone and stitching the torn tendon from the area it had torn away from. In addition, a ligament is also released (coracoacromial ligament), and a prominence on a bone cut away to give the repaired muscle more space in which to move. The strength and size of the repair will vary according to your injury. The operation may be done arthroscopically (keyhole) or through a small incision at the side of the shoulder.

Mr. Cole will discuss your specific situation in more detail with you.

Preparing for your operation

Your rotator cuff repair operation may be done as a day case or more usually will involve an overnight stay in hospital. You may feel more comfortable if you bring your own dressing gown, slippers and toiletries.

You will be having a general anaesthetic. This can make you feel woozy for a little time after the operation, so you will need to arrange for someone to take you home. It is important that you don't eat or drink anything for six hours prior to your admission into hospital, although you may drink water up to two hours prior to admission.

If you normally wear make-up or nail varnish, please remove it prior to your admission. You will also need to bring all prescribed medicines and supplements, in their original containers, with you to the hospital.

Understanding your operation

After admission, you will be seen by Mr. Cole and by your specialist anaesthetist. They will talk about the operation and the anaesthetic with you and, where possible, discuss your preferences. Nothing will be done without your permission on the day.

Anaesthetic and pain relief

The operation is carried out under a general anaesthetic. After your admission, you will be given a pre-med. This is usually in tablet or liquid form. It will help you relax before your operation.

You will then be taken to the anaesthetic room, where you will be given the anaesthetic. This may either be a gas to breathe or an injection. This will be all you remember about the operation, as you will fall asleep at this point and awake after the operation in the recovery room.

Normally you will be given an interscalene nerve block during the operation. This acts as an excellent pain relief and for a short while after your operation your shoulder and arm may feel numb. When this wears off, your shoulder can feel more sore. You will be given some painkillers to take after the operation. When you begin to feel sensation returning to your shoulder (often a "pins and needles" feeling), you should start taking the pain medication that you have been given. Don't wait for your shoulder to start hurting, as pain is best managed before it gets acute. To keep the pain under control, use your medication regularly to begin with. After a couple of days, you can begin to lower the amount you take and then cease the medication altogether once any pain has subsided. If the pain does not seem to get better, or if you need more pain medication, please contact Mr. Cole.

A cold compress can also help with pain relief and swelling at the site of your operation. If you use an ice pack it is important you keep the wounds dry.

Risks

All operations involve a small element of risk. In rotator cuff repairs, these can include:

Complications relating to the anaesthetic such as sickness, nausea or rarely cardiac, respiratory or neurological issues (less than 1% each, i.e. less than one person out of one hundred).

Infection. These are usually superficial wound problems. Occasionally deep infection may occur many months after the operation (less than 1%).

Persistent pain or stiffness in or around the shoulder (10% of patients could still have some symptoms despite the operation).

Damage to the nerves and blood vessels around the shoulder (less than 1%).

A need to re-do the surgery. In some cases it is possible for the muscle to re-tear. The risk of this happening depends on the size of the original injury and how well it heals following the operation.

Please discuss these issues with Mr. Cole if you would like further information.

Recovery

Follow-up appointments

You will usually be invited to attend an outpatient clinic two weeks following your operation, where the wound will be examined and your dressing removed. If you need any stitches removing, this will be discussed with you and, if appropriate a time to do this will be arranged with you (normally at least ten days after your operation).

After about six to eight weeks you will be asked to return so that Mr. Cole can check on your progress. You may discuss any concerns you have during these appointments. Alternatively, should you have a concern, you may telephone Mr. Cole's clinic at any time following your operation.

The wound

Keep the wound dry until it is healed. This is normally for 10 to 14 days. You can shower or wash and use ice packs, but you will need to keep the wound dry. You can protect it with a waterproof dressing. These will be provided to you on your discharge from hospital. Avoid using spray deodorants, talcum powder or perfumes near or on the scar.

The sling

Your arm will be immobilised in a sling for about three to five weeks. It comes with a body strap which keeps your arm close to your body. This is to protect the surgery during the early phases of healing and to make your arm more

comfortable.

You will be shown how to get your arm in and out of the sling. However, you should only take the sling off to wash, straighten your elbow, or if sitting with your arm supported.

You may find your armpit becomes uncomfortable while you are wearing your

sling for long periods of time. Try using a dry pad or cloth to absorb the moisture.

Sleeping

Sleeping may be uncomfortable for a while. It's best to avoid sleeping on the side of your operation. If you choose to lie on the other side, you can rest your arm on pillows placed in front of you. A pillow placed behind your back can help prevent you from rolling onto your operated shoulder during the night. If you are lying on your back to sleep you may find placing a thin pillow or small rolled towel under your upper arm or elbow will enhance your comfort.

Your recovery

Different people recover at different rates. However, by about three weeks following your operation you should find that movement below shoulder height becomes more comfortable. Do not use your operated arm for activities involving weight (e.g. lifting kettle, iron, saucepan) for 8 weeks. Light tasks can be started once your arm is out of the sling. To begin with you may find it more comfortable keeping your elbow into your side. You should also be able to move your arm into most positions, including above shoulder height, although this might still be a little painful.

By three months you should feel a lot better. However, it can take from six to nine months to fully recover. You will continue to improve for up to a year following the procedure.

Driving

You may begin driving approximately six weeks after your operation or when you feel comfortable. Check you can manage all the controls and it is advisable to start with short journeys. The seat belt may be uncomfortable to begin with, but your shoulder will not be harmed by it.

In addition, it is a good idea to check your insurance policy. Many insurers will require you to inform them of your operation.

Returning to work

The best time for you to return to work depends on how you feel following the operation and on the type of work you do. If your job is largely sedentary with minimal arm movements close to your body, you may be able to return between three and five weeks after your operation. However, if you have a heavy lifting job or one with sustained overhead arm movements you may require a longer period of rehabilitation. It is best to discuss this with Mr. Cole and with your physiotherapy team.

Returning to sport and leisure activities

Your ability to start these activities will be dependent on pain, range of movement and strength that you have in your shoulder. It is wise to avoid sustained or powerful overhead movements (such as trimming a hedge, some DIY, racket sports, front crawl) for a few months. These types of movement will put stress on the subacromial area and may take longer to become comfortable. It is best to start with short sessions involving little effort and then gradually increase the effort or time for the activity. Your physiotherapy team will be able to give advice tailored to you and your situation.

Physiotherapy

You will be shown exercises by the physiotherapist and you will need to continue with the exercises once you go home. They aim to stop your shoulder getting stiff and to strengthen the muscles around your shoulder. We have outlined these early exercises here. Your physiotherapy team will also devise a longer term programme tailored for you and your situation.

Use pain-killers, ice packs or both to reduce any pain before you begin exercise, if necessary. It is better to do short frequent sessions of physiotherapy several times a day, rather than one long session. Aim to exercise for five to ten minutes, four times a day.

It is normal for you to feel aching, discomfort or stretching sensations when doing these exercises. However, intense or lasting pain (such as pain that lasts for more than 30 minutes) is an indication to change the exercise by doing it less forcefully or less often.

Post operative exercises

Phase 1 Exercises

(for weeks 3-5)

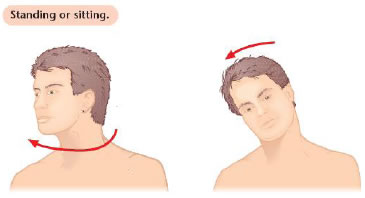

1. Neck exercise (shown for right shoulder)

Do this exercise either sitting or standing

Turn your head and look to the left. Return your head to the centre, facing forward. Repeat 5 times

Turn your head to the other side and look to the right. Return your head to the centre, facing forward. Repeat 5 times

Tilt your head gently and slowly towards one shoulder. Return your head to the centre position. Repeat 5 times

Tilt your head gently and slowly towards the other shoulder. Return your head to the centre position. Repeat 5 times

2. Elbow exercise (shown for left arm)

Do this exercise either standing or lying on your back

Straighten your arm and then bend it at your elbow

Repeat 5 times

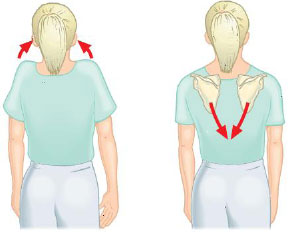

3. Shoulder shrug (shown for both shoulders)

Sit or stand

Slowly shrug both shoulders up and forwards

Roll them gently down and back

Repeat 10 times

4. Pendulum (shown for left shoulder)

Lean forwards with support

Let your arm hang down

Swing arm

1. forwards and back

2. side to side

3. around in circles (both ways)Repeat 5–10 times each movement

5. Arm overhead (flexion in lying) (shown for left shoulder)

Lie on your back on your bed or the floor

Support the arm of your operated shoulder with your other hand at the

wrist and lift it up overheadDo not let your back arch

Try to get your arm back towards the pillow or floor

You can start with elbows bent

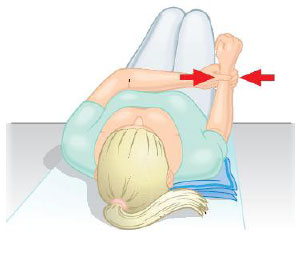

6. Twisting outwards (external rotation) (shown for right shoulder)

Lie on your back, with a folded towel under your operated arm, holding a walking stick, or rolling pin, or umbrella

Keep your elbow into your side throughout

Push with your unaffected arm, so that the hand of your problem side is moving away from the mid-line. Do not over-stretch or let your body twist round to compensate

Repeat 5 times

Phase 2 Exercises

Start these when advised to do so – a minimum of 5 weeks after your operation

1. Arm overhead, with elbows bent (flexion in lying) (shown for right shoulder)

Lie on your back on your bed or the floor, with the elbow of your operated arm bent

Support the arm of your operated shoulder with your other hand at the wrist and lift it up overhead. Once it is vertical, try and keep it there without the support of the other arm

Gradually lower and raise your arm in an arc, until you can lift it from the floor or the bed

Do not let your back arch

Repeat 10 times

After 2 weeks you may be able to progress this exercise by doing the same action standing up

Build it up gradually and try to get your shoulder joint to move

2. Resistance push inwards (shown for right shoulder)

Lie on your back on your bed or the floor, with the elbow of your operated arm close to your side

Hold the wrist of your affected arm with your good hand

Try to move the hand of your operated arm inwards, but prevent it from moving by using the other hand. Hold for 5 seconds

Repeat 5 times and gradually increase to 20 times

3. Resistance push outwards (shown for right shoulder)

Lie on your back on your bed or the floor, with the elbow of your operated arm close to your side

Hold the wrist of your affected arm with your good hand

Try to move the hand of your operated arm outwards, but prevent it from moving by using the other hand. Hold for 5 seconds

Repeat 5 times and gradually increase to 20 times

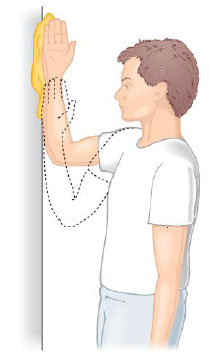

4. Arm overhead (flexion in standing) (shown for right shoulder)

Stand facing a wall with the elbow of your operated shoulder bent and your hand resting against the wall

Slide your hand up the wall, aiming to get a full stretch. (If necessary, use a paper towel between your hand and the wall to make it easier)

Repeat 10 times

Progress by moving away from the wall

5. Arms behind back (shown for right shoulder)

Stand with your arms behind your back

Grasp the wrist of your operated arm

Gently stretch your hand towards the buttock of your un-operated side

Slide your hands up your back

Repeat 5 times

6. Pulley pull (shown for right shoulder)

Sit or stand

Set up a pulley system with the pulley or ring high above you – it is best to have the pulley point behind you

Pull down with your un-operated arm to help life the operated arm up

Repeat 10 times

Phase 3 Exercises

There is a great variation between what different people can achieve during their rehabilitation, so don't worry if you cannot do these exercises or if your physiotherapist gives you different exercises to try. A special programme will be devised for you by your physiotherapy team in consultation with Mr. Cole. They will concentrate on increasing the strength and mobility of your shoulder and will be designed for your specific needs. Work hard at your exercises as improvements in strength can increase for up to two years.

I would like to thank Professor Carr and Jane Moser of the Oxford Shoulder and Elbow Clinic for allowing us to reproduce some of this text and illustrations from their patient information