Overview

What is the acromioclavicular joint?

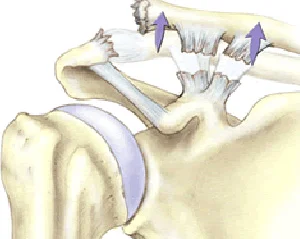

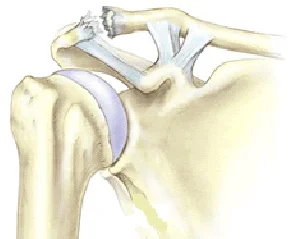

Often referred to as the ACJ, the acromioclavicular joint is the point where the collar bone (clavicle) meets the flat bone at the top of the shoulder blade, known as the acromion. The joint is located on the tip of the shoulder and moves when your arm is overhead or stretching across your chest. The ACJ is held in position by two ligaments (the coracoclavicular ligaments) and cushioned by a thick pad of cartilage, known as the meniscus.

What are the common acromioclavicular joint problems?

The three most common conditions that can affect the acromioclavicular joint are arthritis, stress fractures (osteolysis) and dislocations.

ACJ arthritis is a degenerative disease that can cause a loss of cartilage around the joint. This can lead to irritation, the development of bony spurs, inflammation and pain around the joint.

Stress fractures of the ACJ (also known as ACJ osteolysis) can happen at the outer end of the collar bone, at the point where it joins the shoulder blade.

The acromioclavicular joint can dislocate, just like the shoulder can. It normally happens due to a traumatic injury which causes the ligaments holding the bones of the joint in place to break.

Why do acromioclavicular joint problems happen?

ACJ arthritis

The most common cause of acromioclavicular joint arthritis is wear and tear through over use. For this reason it is most common in people who are aged 50 or older and in athletes who place a lot of stress on the joint – such as rugby players and weight lifters.

ACJ dislocations

The acromioclavicular joint can be dislocated by trauma such a fall directly onto the tip of the shoulder, or by a fall onto an outstretched hand. The degree of dislocation is determined by how many of the ligaments are torn and how far the collar bone has been moved. The severity of the injury can be graded from I-VI

A Grade I injury involves damage to the joint itself with a ‘sprain’ of the capsule. The lateral end of the clavicle is not displaced and other than some swelling at the time of injury there is no cosmetic deformity

A Grade II injury is a partial dislocation of the ACJ with disruption to the joint and possibly damage to the intra-articular meniscus

A Grade III injury involves complete separation of the ACJ. The Conoid and trapezoid (coracoclavicular) ligaments are damages and the end of the clavicle dislocates upwards with a cosmetic deformity

ACJ stress fractures

Repetitive overhead activities that put an excessive weight on the edge of the collar bone can lead to erosion or stress fractures (osteolysis). ACJ stress fractures are most commonly seen in athletes such as rugby players

and weightlifters and in people whose work includes heavy overhead activities, such as builders and plasterers.

How common are acromioclavicular joint problems?

Acromioclavicular joint injuries are most common in athletes who have to carry weight on their shoulders, such as weightlifters, wrestlers and rugby players. This type of injury is also more common in builders and plasterers, who may carry weights overhead, and in older people who may suffer from additional wear and tear and arthritic change to their joints.

Symptoms

ACJ arthritis

The symptoms of ACJ arthritis are similar to those of arthritis in other joints of the body. They include stiffness, pain, restricted movement, swelling and redness of the affected area. Pain is often felt directly over the ACJ and may disrupt sleep.

ACJ dislocations

Pain, especially on movement of the shoulder, and a clicking sound from the tip of the shoulder are common symptoms of an ACJ dislocation. There may also be a prominent bump at the tip of the shoulder. The size of the bump depends on the severity of the disruption.

ACJ stress fractures

Symptoms of ACJ stress fractures include tenderness or pain at the point of the joint. It may also be painful to stretch the arm of the affected shoulder across the body.

Investigating the problem

Physical examination

Mr. Cole will talk to you about your shoulder symptoms and your shoulder's history. He will examine your shoulder and assess your range of movement. He will use a number of diagnostic clinical tests and possibly inject you ACJ to make a diagnosis

X-ray

X-rays can provide excellent pictures of the bones and are a good way of identifying stress fractures, dislocations and bony spurs that have developed as a result of arthritis. X-rays will be done in most cases and are often enough to make a diagnosis along with the clinical signs.

MRI

MRI stands for Magnetic Resonance Imaging. It uses a powerful magnet to obtain three dimensional pictures of body structures. It is a non-invasive and painless procedure. It is an excellent way to visualise the ACJ. It will show damage to the cartilage, ligaments, muscles and tendons. It is particularly useful to diagnose osteolysis and damage to the coracoclavicular ligaments after a traumatic injury.

Treatment options

Non-surgical treatment

ACJ arthritis

Physiotherapy will form a key part of your treatment and rehabilitation. In consultation with Mr. Cole, your team of physiotherapists will devise a programme of exercises for you that are designed to prevent any further stiffness and help you to regain your range of motion.

You may be offered painkillers and anti-inflammatory medication to help control the pain and reduce the swelling. This medication may take the form of an injection directly into the damaged joint.

ACJ dislocations

If you have only sprained your acromioclavicular joint or have a minor tear of one of the ligaments it is likely that you will not need to have an operation. Treatment will include painkillers to make you feel more comfortable and anti-inflammatory medicine to reduce any swelling. A course of physiotherapy will be devised for you to help strengthen your shoulder muscles, so that they offer greater stability. Your symptoms are likely to resolve over a number of weeks to months. In only a few cases will the pain persist longer and a surgical procedure to stabilize the joint may be considered

ACJ stress fractures

The vast majority of stress fractures in the acromioclavicular joint heal well by themselves with a period of complete rest from overhead activities and heavy lifting. You would typically expect bones to heal in about six weeks. You may be offered painkillers and anti-inflammatory medication as appropriate. Your team of physiotherapists will also devise a programme to help strengthen the muscles around your joint. This will help support the joint and may also provide you with some pain relief.

Surgical treatment

ACJ arthritis

Operations are rarely needed in cases of ACJ arthritis. However, if your arthritis is particularly advanced and painkillers are not managing to make you comfortable, Mr. Cole may feel it is appropriate for you. He will discuss your operation directly with you, and your treatment may involve a procedure such as an ACJ excision. This involves the removal of part of the damaged ACJ joint and is normally completed as keyhole (arthroscopic) surgery. This operation will be successful in eliminating symptoms in 90% of the time and can be done as day case surgery

ACJ dislocations

If your collar bone is no longer connected to your shoulder blade, you may need a surgical procedure to repair the damaged ligaments and return your collar bone to its correct position. This is done by re-routing another

ligament (the coracoacromial ligament) to the end of the collar bone to stabilize the joint.

You may also need surgery if you have a sprain or a minor tear that does not heal properly within three to six months. In these cases, for example, your joint may continue to cause you pain or you may have trouble with your range of movements. The operation would usually be completed as keyhole surgery (arthroscopic) or through a small incision, you would not normally need to stay overnight in hospital.

ACJ stress fractures

If your condition fails to heal adequately on its own, Mr. Cole may discuss the need for an operation with you. The procedure, called an ACJ excision, is the same as that sometimes needed in cases of severe arthritis. It involves the removal of part of the damaged ACJ joint and is normally completed as keyhole (arthroscopic) surgery.

Exercise

Following your surgery, your team of physiotherapists will work with you to devise an exercise programme. This will be designed with advice from Mr. Cole to help you recover as quickly and efficiently as possible.

Surgery

About acromioclavicular joint excision

ACJ arthritis is a degenerative disease that can cause a loss of cartilage around the joint. This can lead to irritation, the development of bony spurs, inflammation and pain around the joint. It can happen without any specific cause or can be due to a previous traumatic injury. Operations are rarely needed in cases of ACJ arthritis. However, if your arthritis is particularly advanced and painkillers are not managing to make you comfortable, Mr. Cole may feel it is appropriate for you. He will discuss your operation directly with you, and your treatment may involve a procedure such as an ACJ excision. This involves the removal of part of the damaged ACJ joint and is normally completed as keyhole (arthroscopic) surgery. Approximately 5mm of the end of the clavicle is excised This operation will be successful in eliminating symptoms in 90% of the time and can be done as day case surgery. The operation is likely to be completed as keyhole surgery (arthroscopic) but open surgery may be considered depending on the nature of your precise problem

Preparing for your operation

Regardless of whether your operation is open surgery or keyhole surgery, you should only have to stay in hospital for the day, although you may wish to stay overnight. You may feel more comfortable if you bring your own dressing gown, slippers and toiletries.

You will be having a general anaesthetic. This can make you feel woozy for a little time after the operation, so you will need to arrange for someone to take you home. It is important that you don’t eat or drink anything for six hours prior to your admission into hospital, although you may drink water up to two hours prior to admission.

If you normally wear make-up or nail varnish, please remove it prior to your admission. You will also need to bring all prescribed medicines and supplements, in their original containers, with you to the hospital.

Understanding your operation

After admission, you will be seen by Mr. Cole and by your specialist anaesthetist. They will talk about the operation and the anaesthetic with you and, where possible, discuss your preferences.

Anaesthetic and pain relief

The operation is carried out under a general anaesthetic. After your admission, you may be given a pre-med. This is usually in tablet or liquid form. It will help you relax before your operation.

You will then be taken to the anaesthetic room, where you will be given the anaesthetic. This may either be a gas to breathe or an injection. This will be all you remember about the operation, as you will fall asleep at this point and awake after the operation in the recovery room.

You may be given an interscalene nerve block during the operation. This acts as an excellent pain relief and for a short while after your operation your shoulder and arm may feel numb. When this wears off, your shoulder can feel more sore. You will be given some painkillers to take after the operation. When you begin to feel sensation returning to your shoulder (often a ‘pins and needles’ feeling), you should start taking the pain medication that you have been given. Don’t wait for your shoulder to start hurting, as pain is best managed before it gets acute. To keep the pain under control, use your medication regularly to begin with. After a couple of days, you can begin to lower the amount you take and then cease the medication altogether once any pain has subsided. If the pain does not seem to get better, or if you need more pain medication, please contact Mr. Cole.

A cold compress can also help with pain relief and swelling at the site of your operation. If you use an ice pack it is important you keep the wounds dry.

Risks

All operations involve a small element of risk. In ACJ procedures these may include:

Complications relating to the anaesthetic such as sickness, nausea or rarely cardiac, respiratory or neurological issues (less than 1% each, i.e. less than one person out of one hundred).

Infection. These are usually superficial wound problems. Occasionally deep infection may occur many months after the operation (less than 1%).

Persistent pain or stiffness in or around the shoulder (5% of patients could still have some symptoms after the operation).

Damage to the nerves and blood vessels around the shoulder (less than 1%).

The need to re-do the surgery is rare. In less than 5% of cases.

Please discuss these issues with Mr. Cole if you would like further information.

Recovery

Follow-up appointments

You will usually be invited to attend an outpatient clinic a few weeks following your operation, where the wound will be examined and your dressing removed. After several months you will be asked to return so that Mr. Cole can check on your progress. You may discuss any concerns you have during these appointments. Alternatively, should you have a concern, you may telephone Mr. Cole’s clinic at any time following your operation.

The wound

ACJ excision is likely to have been performed as keyhole (arthroscopic) surgery. If the procedure is arthroscopic, you will have some small puncture wounds. You will not have any stitches, only small sticking plaster strips. If the procedure involves open surgery, you will have stitches. These will probably be soluble, which means they won’t need to be removed, but Mr. Cole will advise you of this.

Keep the wounds dry until they are healed. With arthroscopic surgery, this is normally within five to seven days. Open surgery wounds take a little longer to heal, normally 10 days or so. You can wash or shower and use ice packs, but protect the wounds with a waterproof dressing. You will be given these on your discharge from hospital. Avoid using spray deodorant, talcum powder or perfumes near or on the wounds until they are well healed. The dressing will normally be removed for good at your first follow-up appointment.

The sling

Your arm will be rested in a sling for a few days only. You can take your arm out of the sling as soon as it is comfortable enough. You will be guided by your physiotherapist on the exercise regime that is suitable for you. You may find your armpit becomes uncomfortable while you are wearing your sling for long periods of time. Try using a dry pad or cloth to absorb the moisture.

Sleeping

Sleeping may be uncomfortable for a while. It’s best to avoid sleeping on the side of your operation. If you choose to lie on the other side, you can rest your arm on pillows placed in front of you. A pillow placed behind your back can help prevent you from rolling onto your operated shoulder during the night. If you are lying on your back to sleep you may find placing a thin pillow or small rolled towel under your upper arm or elbow will enhance your comfort.

Your recovery

Different people recover at different rates. By six weeks you should feel a lot better and hopefully the operation will be considered a success. However, it can take on average from three to six months to fully recover. You may continue to improve for up to a year following the procedure.

Driving

You will should be able to drive again within 1-2 weeks following the surgery. When you do take your first journey after your surgery, it is a good idea to check you can manage all the controls. It is also advisable to start with short journeys.

Returning to work

The best time for you to return to work depends on how you feel following the operation and on the type of work you do. If your job is largely sedentary with minimal arm movements close to your body, you may be able to return after a short period. If you have a heavy lifting job, or one with sustained overhead arm movements, you will require a longer period of rehabilitation, possibly up to three months. Mr. Cole and your physiotherapy team will discuss this with you.

Returning to sport and leisure activities

Your ability to start sporting activities will be dependent on pain, range of movement and strength that you have in your shoulder. It is best to start with short sessions involving little effort and then gradually increase the effort or time for the activity. Your physiotherapy team will be able to give advice tailored to you and your situation. As general guidance, however, you can expect to have to wait a minimum of two weeks before swimming breaststroke, and 6 weeks for most other sports including golf, horse riding, rugby, football and racquet sports.

Physiotherapy

You will be shown exercises by the physiotherapist and you will need to continue with the exercises once you go home. They aim to stop your shoulder getting stiff and to strengthen the muscles around your shoulder. We have outlined these early exercises here. Your physiotherapy team will also devise a longer term programme tailored for you and your situation.

Use pain-killers, ice packs or both to reduce any pain before you begin exercise, if necessary. It is better to do short frequent sessions of physiotherapy several times a day, rather than one long session. Aim to exercise for five to ten minutes, four times a day.

It is normal for you to feel aching, discomfort or stretching sensations when doing these exercises. However, intense or lasting pain (such as pain that lasts for more than 30 minutes) is an indication to change the exercise by doing it less forcefully or less often.

Post operative exercises

Phase 1 Exercises

You can begin these exercises immediately after your operation.

1. Pendulum (shown for left shoulder)

Lean forwards with support

Let your arm hang down

Swing your arm forwards and back

Repeat 5–10 times each movement

2. Lower trapezius (shoulder blade exercises) (shown for both shoulders)

Do this exercise either sitting or standing

Keep your arms relaxed

Square your shoulder blades (pull them back and slightly down)

Do not let your back arch

Do not let elbows move backwards (you can clasp your hands in front of you, to discourage this!)

Hold for 10 seconds

Repeat 10 times, “little and often” during the day

3. Twisting outwards (external rotation) (shown for right shoulder)

Sit holding a walking stick, or rolling pin, or umbrella

Keep your elbow into your side throughout

Push with your unaffected arm, so that the hand of your problem side is moving away from the mid-line (you can also do this exercise lying down)

Do not let your body twist round to compensate

Repeat 5–10 times

4. Arm overhead (flexion in lying) (shown for left shoulder)

Lie on your back on your bed or the floor

Support the arm of your operated shoulder with your other hand at the wrist and lift it up overhead

Do not let your back arch

Try to get your arm back towards the pillow or floor

You can start with elbows bent

Repeat 5–10 times

5. Arm overhead (flexion in standing) (shown for right shoulder)

Stand facing a wall with the elbow of your operated shoulder bent and your hand resting against the wall

Slide your hand up the wall, aiming to get a full stretch. (If necessary, use a paper towel between your hand and the wall to make it easier)

Repeat 10 times

6. Shoulder blade exercise (shown for right shoulder)

Lie on your front, with your head face down supported by a rolled-up towel under your forehead, or with your head turned towards your operated shoulder

Keep your arms relaxed by your side

Lift your shoulder straight up in the air. Try and keep a gap approximately 5cm between the front of your shoulder and the bed or floor you are lying on

Hold your shoulder up for 30 seconds

Repeat 4 times

You may progress this exercise by lifting your arm up and down (elbow straight) while keeping the shoulder blade up all the time

I would like to thank Professor Carr and Jane Moser of the Oxford Shoulder and Elbow Clinic for allowing us to reproduce some of this text and illustrations from their patient information